Join us at The Cove this Summer!

Join us for a week of teaching, time with God, fellowship, nature, and more at The Cove: A Billy Graham Training Center. July 21-25, 2025!

Read MoreBy Tim Keller

The ancients saw history as repetitious and endless. Their image of time was a wheel, in that the ages of the world repeated themselves in great cycles. The Hindu Vedas, for example, taught that the universe goes through great arcs of creation, rise, decline, destruction, and then rebirth, each of which last millions of years, and which go on forever without any resolution. Christianity, however, understands history to be under the control of God who is moving it purposefully toward a great and irreversible climax.

Late modern secular culture has rejected religion and even belief in God, yet has held on tightly to the Christian-inspired idea that history is making progress. The people once called “liberals” now call themselves “progressives,” which shows how deeply the Christian idea has embedded itself in our thinking. Secular westerners do not simply believe that we can make things better in this or that area, but that “the times” are inevitably moving the world to a better condition. We often denounce actions or positions as “having no business in the 21st century,” or as “archaic thinking out of step with the times.”

The problems with this viewpoint are obvious, however. Do we really want to say that every historical trend is a good one? And if you can think of any thing happening now more than in the past that you believe is bad or wrong, then that destroys the idea that whatever is new is better than what it displaced. Partly because of these kinds of problems, a great debate over whether history is really making progress has arisen in the last two decades.

Silicon Valley and others maintains the idea that science and technology inevitably make the world better. Many excited voices there describe a future in which the problems of aging, disease, poverty, and inequality are all solved or transformed.

On the other hand there, the old hopefulness about the future has disappeared. For the first time Americans are saying that their children’s lives probably will not be better than their own. Also, a remarkable number of recent films depict a dystopian future in which civilization is largely decimated. There is pessimism among many that technology is removing our privacy, dehumanizing us, and making us vulnerable to future terrorism and to exploitation on an unprecedented scale.

The Christian answer to all this is two-fold. First, we can say that, by the standards of the Bible, the modern idea of historical progress has been too optimistic about both history and human nature. It assumes that the new is always better, which common sense tells us is not the case. C.S. Lewis in Surprised by Joy called this kind of thinking “chronological snobbery,” namely “the assumption that whatever has gone out of date is on that account [alone] discredited.”

This is not just foolish, it is dangerous. It makes it possible for people to argue that whatever is new, despite its triumphalism and cruelty, is right. The Nazis were sure that they were on “the right side of history” as were the communists. Indeed, from about 1920 through World War II, most intellectuals and academics in western society thought Marxism was the inevitable future. History is completely inadequate as a moral guide.

However, many in our postmodern era are too pessimistic. They have rejected the idea of progress for the idea that history is “a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury signifying nothing.”

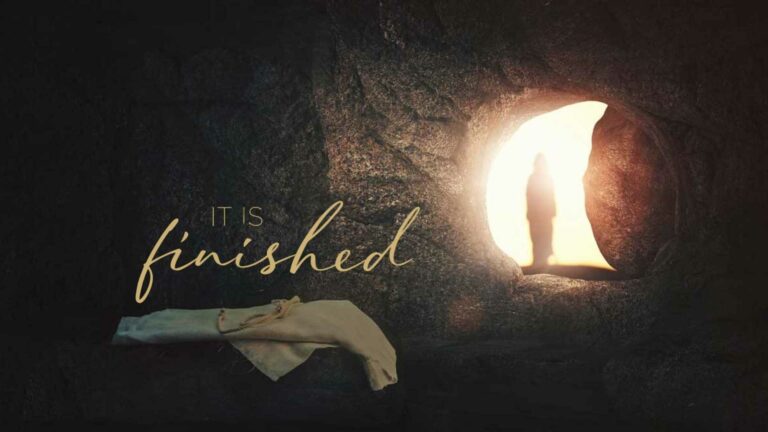

The Christian answer to the overly optimistic or overly pessimistic modern views of history is the Resurrection. Christianity, paradoxically, is far more pessimistic and far more optimistic than any other worldview — simultaneously. On the one hand, the Christian view of human sin is that we are deeply flawed and can’t save ourselves and we may indeed have some terribly bad stages of history ahead. No other religion has as dark a view of human depravity. We are capable of great evil.

But the Christian promise is not that every chapter in history will be better than the first but that in the end “all things will work together for good.” God will eventually bring us not to a disembodied afterlife, but a renewed material universe with resurrected bodies. That, again, is something only biblical religion promises.

History ends with the resurrection. Resurrection is complete restoration, but only after death and destruction. This avoids the unbalanced optimism of modernity but also the hopelessness of dystopianism. On the final day of history, we know that our Redeemer will stand upon the earth, and that in our new resurrected bodies we will see God (Job 19:25-26). In the words of the poet Seamus Heaney “The longed-for tidal wave of justice can rise up — and hope and history rhyme.”

https://timothykeller.com/blog/2015/4/4/when-hope-and-history-rhyme

This article appears at www.timothykeller.com. Used with permission by the author.

Timothy Keller is the founding pastor of Redeemer Presbyterian Church in Manhattan, chairman of Redeemer City to City, and author of multiple books including Hope in Times of Fear: The Resurrection and the Meaning of Easter.

Join us for a week of teaching, time with God, fellowship, nature, and more at The Cove: A Billy Graham Training Center. July 21-25, 2025!

Read More

As we observe Holy Week and celebrate our Risen Savior, I wanted to let you know that our Walk Thru the Bible President, Phil Tuttle, will be preaching the Good Friday Service (Friday, April 18) as well as the Easter Sunrise Service at the Garden Tomb in Jerusalem this Sunday.

Read More