Join us at The Cove this Summer!

Join us for a week of teaching, time with God, fellowship, nature, and more at The Cove: A Billy Graham Training Center. July 21-25, 2025!

Read MoreObserving my son’s suspense was painful enough to watch when he was viewing the movie for about the twentieth time, but it was excruciating to observe him when he saw it for the first time. Would the kingdom be saved, or would the only possible rescuer succumb to the overwhelming odds against him? Would evil be defeated, or would the princess sleep and the land lie in darkness forever? Were a sword, bravery, and some fairy dust enough to overcome chains, fiery breath, and a curse? It was all up in the air, and an entire kingdom hung in the balance.

Fortunately, my son’s suspense was resolved in less than an hour and a half of recorded video. I’ve wondered, though, what it would be like if the hero in that story—or any other suspenseful drama—could interact with the storyteller who’s calling all the shots. How would the dialog sound if the main character could have a conversation with the writer as the plot develops?

“If it’s my calling to rescue her, why is everything moving in the opposite direction? How can I kiss her if I’m chained in a dungeon and she’s comatose in a far-away tower? How utterly senseless. Are you sure you know what you’re doing? Oh, I get it now. The fairies break me out of the dungeon—glad that’s done. Wait a minute; it’s not over yet? So let me get this straight: against all odds, I’ve just exhausted myself working my way through a field of deadly thorns—and now I’ve got to defeat a nasty dragon while standing on the edge of a staggering precipice? Are you kidding me? Would it be too much to have a minute to breathe? What kind of storyteller are you? Cruel. Sadistic. And obviously not on my side.”

The problem for the hero who utters such words is his limited perspective. He’s speaking while the plot is still at the height of dramatic tension, before everything has been resolved. The storyteller knows how it will end, but the hero still has to fight his battles. And from where he sits, the battles could go either way. The stakes are high, and the outcome is shaky.

We know that in the world of fiction, greater calamities in the middle of a story make for greater victories and celebrations at the end of it. No one leaves a theater in tears of joy after watching the main character work through a minor setback. No, we love impossible odds and astounding victories, and we can’t have the latter without the former. The darker things get in the middle, the brighter things look in the end. The trauma sets up the triumph. This is what makes a story good.

The trauma sets up the triumph. This is what makes a story good.

I’ve thought about this a lot because the son who used to love Prince Philip’s story has had quite a few battles to fight in recent years, particularly after a car accident left him with life-altering injuries. He knows the end of the big story—that good defeats evil—but he doesn’t know the end of his story, at least as it plays out in his earthly lifetime. And the suspense is excruciating. In so many ways, the odds are against him. He has been through a lot, and from where he sits, he could easily judge the storyteller in the middle of the story. He could lament the brutal plot twists and assume that the writer is against him. He could deem the story a disaster.

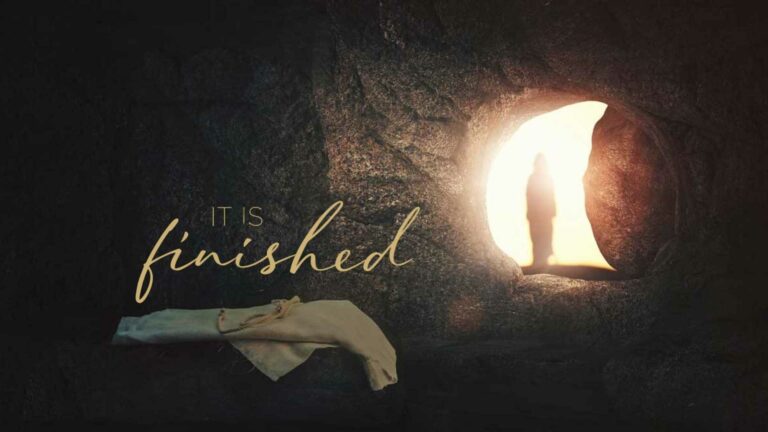

I have a tendency to judge God in the middle of my story too. In various times in my life, I’ve made some pretty pointed statements against Him. Like Job, I’ve wondered why He has abandoned me. Like Jeremiah, I’ve accused Him of deceiving me. Like Jesus on the cross, I’ve cried out that He has forsaken me. It’s natural for those of us with limited perspective to do such things. We don’t see the end of the story.

This is essentially the trajectory taken by Edmond Dantès, the main character in The Count of Monte Cristo. Betrayed by his best friend, he is unjustly imprisoned and loses his fiancée to the betrayer. For years, he sits in one of France’s most formidable island prisons and thinks about his plight. Day after day, he carves into the wall: “God will give me justice.” The words get deeper each year, but the conviction that they are true does not. In fact, by the time of his escape after 13 years in prison, he is convinced that there is no God after all. Like many human beings, he has judged God in the middle of the story because the plot seemed too difficult to bear.

Much of the Christian life is a matter of perspective. The narrower and shorter our view gets, the worse things can look. The longer our view gets, the more optimistic we become. Why? Because we are given great and precious promises of ultimate victory. The very worst that can happen to those who believe in Jesus is a few decades of hardship and then an entrance into a kingdom in which there are “eternal pleasures” at God’s right hand (Psalm 16:11). We are assured of a crown of life (James 1:12; Revelation 2:10) and an incorruptible inheritance (1 Peter 1:4). The promises of God are extravagant beyond our comprehension. And though we get tastes of them in the middle of the story—because there are lots of nice plot twists too, after all—we get the full array at the end.

If you’re in one of those dark times in the middle of the story, take heart. Don’t judge the Storyteller; the story isn’t over yet. We will see the goodness of the Lord both in the land of the living (Psalm 27:13) and beyond. Be patient for the denouement of your life’s plot. And never forget that in all good stories, curses are broken, princesses awake, and everyone dances their heart out in the end.

*****

by Chris Tiegreen

Join us for a week of teaching, time with God, fellowship, nature, and more at The Cove: A Billy Graham Training Center. July 21-25, 2025!

Read More

As we observe Holy Week and celebrate our Risen Savior, I wanted to let you know that our Walk Thru the Bible President, Phil Tuttle, will be preaching the Good Friday Service (Friday, April 18) as well as the Easter Sunrise Service at the Garden Tomb in Jerusalem this Sunday.

Read More